Australia could ‘dodge recession bullet’, says AMP

Falling inflation, household savings and the possibility of rolling sectoral recessions could see Australia avoid a recession, the bank says.

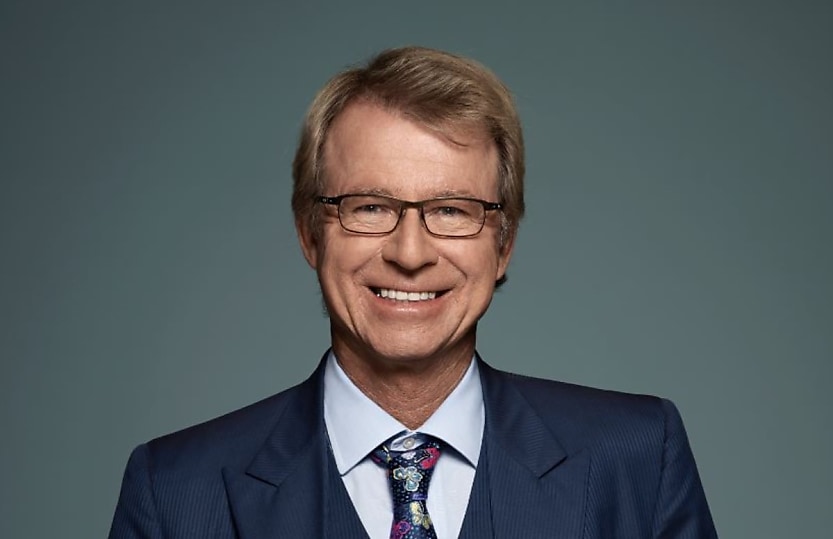

Despite the considerable discussion about a recession both globally and in Australia, growth has generally remained resilient suggesting that Australia may be able to avoid one, according to AMP chief economist Shane Oliver.

With inflation slowing, Dr Oliver said there has been increased talk of a ‘Goldilocks economy’ where growth is stable and inflation is falling.

The base argument for a recession is that major countries have seen the most rapid monetary tightening in decades and that cost-of-living pressures are increasing, he said.

While there are various signs supporting this, there are also other ways a recession could be avoided.

One of the indications that a recession could arise is that the US yield curve has started to invert with short term interest rates rising above long-term rates, last year.

“This has preceded all US recessions over the last 60 years,” said Dr Oliver.

“[However], the first point to note is things like yield curves and leading indicators can get it wrong in forecasting recession.”

There are several issues with using yield curves as a prediction for recession including the fact that the lag from the yield curve inversion in the US can be 18 months, he said.

“US yield curve inversions have given false signals in the past such as in 1998. Inverted yields curves have been a poor indicator of recession since 1991 in Australia and right now it’s not decisively inverted anyway.”

Dr Oliver said its also possible that inflation could fall quickly, taking pressure off rates.

This could occur due to easing goods supply pressures and transport costs, falling job vacancies and an easing in reopening demand taking pressure off wages growth and services inflation.

A productivity surge through artificial intelligence could also help.

“In other words, today’s low unemployment levels could turn out to be consistent with ‘full employment’ and only a marginal cooling in demand may be necessary to return labour and product markets to balance. And so central banks may soon be able to move towards lowering interest rates,” he said.

“Recently the news on this has been good. US inflation has fallen from a peak of 9 per cent year on year to 3 per cent and Australian inflation has fallen from 8 per cent year on year to 6 per cent. This has occurred without a rise in unemployment.”

However, there are still a number of risks for inflation including the risk that services price inflation may prove sticky with wages growth still picking up in some countries.

“This is clearly a risk in Australia with a faster rise in minimum and award wages this year resulting in a renewed surge in labour costs in the latest NAB survey.”

Dr Oliver said the fact that many households still have pandemic savings buffers could also help Australia avoid a recession.

“Through the pandemic people were constrained from spending but most still received an income. The result was that household saving rates rose above normal levels resulting in excess saving. In Australia it has been run down but remains high at around $230 billion,” he said.

“My concern has been and remains that it is not distributed equally and that for many younger (25-45 year old) households with high debt levels it has been rundown such that it’s no longer of any support in the face of the surge in interest payments.

Australia could see rolling sectoral recessions

With different sectors of the economy impacted at different times by shocks like tighter monetary policy, Dr Oliver said various sectors of the economy may have recessions but at different times so that the overall economy never actually contracts.

“Something like this happened through the 1990s and 2000s to varying degrees providing support for the view that the environment back then was characterised by micro instability but overall macro stability and hence milder economic cycles,” he said.

In the US, in this cycle home building and technology, and more recently manufacturing, have arguably already had recessions but they are now starting to find a floor so if consumer spending on services turns down it may be offset by an improvement in home building, technology and manufacturing, said Dr Oliver.

“Similarly in Australia, home building and retailing have been in recession for a while and conceivably could start to recover as consumer spending on services top out,” he stated.

“The risk is high that currently weaker sectors don’t recover in time to offset weakness in lagging sectors like services.”

Strong population growth may also boost demand and therefore GDP growth, which would enable Australia to avoid a recession as defined as a fall in GDP to be avoided.

“In this regard it’s notable that while both the Australian Government and RBA are forecasting positive GDP growth this financial year on a year average basis at 1.5 per cent and 1 per cent respectively, this is expected to be below the rate of population growth at around 1.7 per cent or more which means that both are forecasting a per capita (or per person) recession, but this is masked by strong population growth,” said Dr Oliver.

While each of these considerations have qualifications, together they suggest that Australia could potentially “dodge the recession bullet”.

“[However] it’s a high risk with the lagged impact of rate hikes still feeding through – particularly in Australia where we put the risk of recession at 50 per cent given the vulnerability of the household sector,” said Dr Oliver.

“Weak growth in China is also adding to the risks of recession.”

About the author